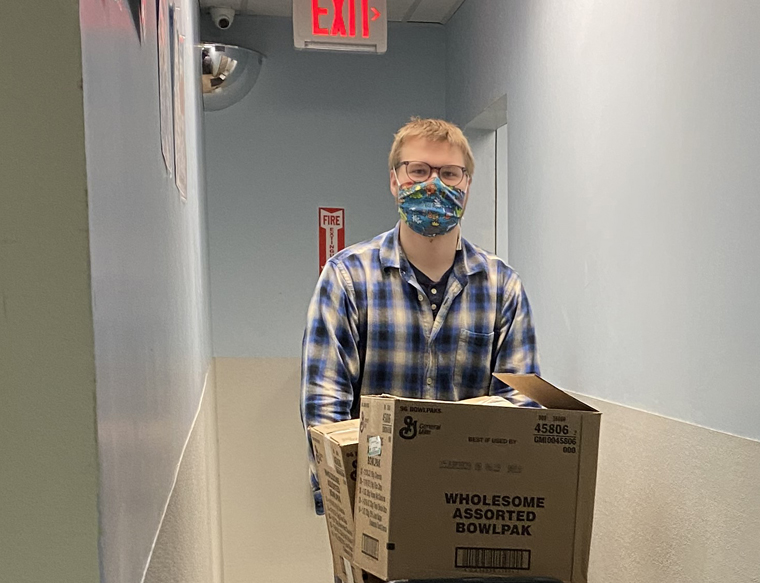

A staff member at Catholic Charities of Onondaga County’s men’s shelter in Syracuse works during the pandemic. (Photo provided)

By Renée K. Gadoua | Contributing writer

Michael Melara apologies for the awkward metaphor he uses to describe Catholic Charities’ challenges during a pandemic characterized by respiratory distress.

“It’s almost like being oxygen deprived,” he said. “We’ve been oxygen deprived when it comes to being in the physical presence of the people we serve. … It’s core to our identity. It’s just part of our DNA.”

COVID-19 restrictions eliminated — or significantly changed — face-to-face program service in the Syracuse Diocese’s six Catholic Charities regions.

“Everything we do in terms of serving those members of our community who are most vulnerable and in greatest need, we do it face to face,” said Melara, diocesan Catholic Charities CEO and executive director of the Onondaga County agency. “And the same is true for staff. The same was true for how we interacted with each other.”

That world turned upside down in about a week last March, when officials closed businesses and schools to prevent spreading a new virus that caused a disease doctors did not know how to treat.

“We had to learn to adapt to this very new environment for us, which was remote work and telecommuting and virtual meetings,” he said. “At the same time, we had to maintain our goal and our mission, which is to stay connected to the people that we serve and stay connected with each other.”

Catholic Charities serves 100,000 people a year. Programs and services include marriage and family counseling, psychotherapy, adoption services, emergency services, parent aid services, residential facilities, nutrition programs, and youth activities.

“When we are out in the community, when we go to a person’s home to work with them, we learn so much about their existence,” Melara said. “Is there food on the shelves? Is the apartment clean? Are there enough toys for the kids? You can see all of that, touch all of that, and know all of that in a very intimate way. And I think that helps to break down the barriers to providing good service because you are allowing yourself to be part of that person’s experience.”

Catholic Charities shifted quickly to remote work.

“We’ve had to make a lot of adjustments this year to do work more remotely,” he said. “What we’ve learned is that we can make adjustments to the way that we work with each other and with the people that we serve.”

The homeless shelter for men, food pantries, and emergency services required face-to-face operation throughout the pandemic.

“There were so many unknowns and challenges in operating a place like the men’s shelter, and our food pantries, and we had to figure it out and figure it out really quick, because if we didn’t, people were going to get sick and as we’ve learned, people have died from COVID, right, lots of people,” he said. “The stakes were just extraordinarily high, particularly in those programs.”

He and other managers have grown to appreciate flexible work arrangements. “I do think that the COVID pandemic has helped us to redefine or continue to redefine what the workplace looks like and the relationship that we have with work,” he said.

“Some of our practices I think are just going to permanently change,” he said, citing board meetings as one example.

He considers managers’ jobs “to do whatever we can to reduce the anxiety of the folks who work for us because their jobs are super hard.”

Efforts included a dedicated email account that quickly responded to employees’ questions about COVID or questions they have about coming back to work, virtual meetings, and educational programs on mental health and safety.

All Catholic Charities offices have reopened, and face-to-face programming and services have resumed. Of 1,400 employees across the diocese, about 40 were diagnosed with COVID-19. Staff, including Melara, have received vaccines.

“I think of our universal pre-K teachers who had to do so much of their work remotely, and how excited they were when kids could come back to the classroom,” he said. “We can breathe a little bit more freely now.”