By Tom Maguire | Associate editor

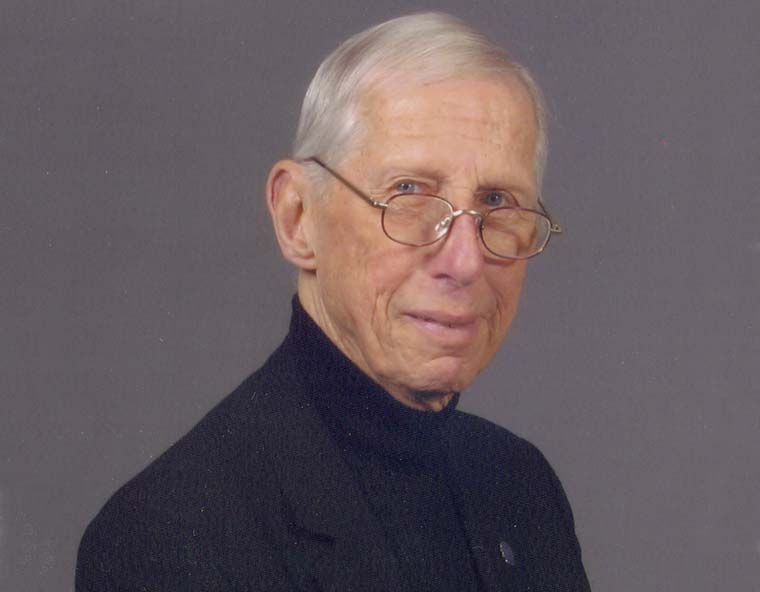

It would be somewhat odd to see a Jesuit climbing trees on the Le Moyne College campus, and in any event Father Paul Naumann’s knees and inclinations are beyond that stage.

But when he started out as a writer he had to approach the task from what he knew — and he knew all about hustling up a maple or an evergreen. The term “white pine” popped into his head one day, and then it popped out again as his first book: Crispin and the Great Tree.

Now the retired English professor has finished 18 books, of which eight have been self-published. He’s working on getting the other 10 out there.

There are eight total Crispin books in Father Naumann’s historical-fantasy series. The one that started it includes a dangerous forest, a philosophical falcon, a wolf with a cauldron, a leopard with lethal teeth, and a “wise and kind” boy.

The ready-for-adventure boy depicted on the cover of the book does indeed look a little like Father Naumann did as a boy, although he was “probably skinnier.”

The author, who goes by the name P.S. Naumann, S.J., summarizes the book this way:

“In 1930, young Crispin (7&1/2) disobeys his parents by entering the forest and climbing the towering great White Pine tree he can see from a window in his home. A few days later he discovers that, to save the great tree from a galloping deadly disease, he must set out on a quest, which he has only two days left to achieve. …

“The wicked Archduke Axel, the so-called ‘Leopard of Tryce,’ continually threatens to prevent Crispin from saving the great tree. In a race against time the boy and his companion, Blight, careering around the country in [a] Pierce-Arrow, try to follow cryptic clues that the Leopard of Tryce has devised in order to ensure that the time will run out, and the tree will come down.”

Naturally, religious references appear in the book. They include the mysterious Monks of Harklinden, “hooded figures in long robes”; prayers for assistance; a reference to thirty pieces of silver; and the Abbot of Our Lady of Harklinden.

Even the exclamations are tinged with a respect for religion. “By the Lord, Crispin, you’ve got the guts of a grown man inside you there,” the boy’s friend Blight tells him. There is also an echo of the Bible when an evil character tempts Crispin by saying he will make him “Lord of the Great Forest.”

If the book has a fair amount of religion, it’s religion with a set of hiking boots and an eye for the top of the tree. It’s religion with an appreciation for the hearty and the daring. If this kid’s a book-lover, he’s also a doer, which counts when one is on a quest.

The forest does pose dangers but it also pulses with hope, and it’s just an inspiration away: Find the right tool, recite the right riddle, remember the right clue, and get to work. No wonder this kid sleeps so soundly: He earns it.

In a later book in the series, Crispin goes on to become a monk himself. Father Naumann said that he writes his books for “middle grade through assisted living. Because there’s something in there for everyone, everybody.”

Everybody can appreciate the first book’s classic childhood delights: milk, chocolate cake, and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Peanut butter, the reader learns, can easily overcome the nefarious intentions of the halfhearted henchman of a leopard. Give a kid a river and a forest and he is just bound to have adventures, with wax-paper-wrapped goodies sustaining him all the way.

And the book’s place names — with their whimsy and improbability — symbolize the exciting potentialities of childhood. Guts for a kid is conversing with a wolf and deciding whether those big eyes hold hunger or helpfulness. Guts is talking to a wolf as an equal and a witch as a candidate for the boiling-water cauldron.

Asked how he comes up with his stories, Father Naumann said, “I’m sure most people who write use what they know. … Basically you use everything that you can: Change, moderate, modify, what have you. But if you can use it, you’ll use it.”

For example, he uses the times of his childhood. His family consisted of his father, Marshall O. Naumann; his mother, the former Helen Mary Schiller; and his siblings: older brother Marshall O. Naumann Jr. and younger brother Ronald A. Naumann. Ronald is still living. He is a retired Syracuse neurosurgeon who lives in Hilton Head, S.C.

The family lived in Syracuse, the Albany area, back in Syracuse, and Baldwinsville.

“We used to spend the summers on the north shore of Oneida Lake,” Father Naumann recalled. “We had a cottage out there.”

To climb a tree, he said, one must “get to the lowest branch and hang a leg over something and pull yourself up.”

There was a big maple tree in the lot next door, “and this gets into the book,” he said.

“I was at the top, and I heard my mother calling: ‘Paul, where are you? Paul!’ And because it was a tall tree I knew I couldn’t get down; I had to answer before I could get down. And so I said, ‘Here I am!’

“‘Are you up that tree?’

“I said, ‘Yeeeesss,’ already starting to climb down.

“It’s something about sitting up in a tree — you can look out, and that sort of thing. If you’ve got a buddy who’s sitting on the branch opposite, that helps.”

Young Paul and his pals built a quasi-tree-hut with an old wooden dock that had washed ashore, but it never amounted to much. “I have no idea what happened to it,” Father Naumann said. “I hope it didn’t fall on anybody.”

It’s that dry wit — a sense of irony — that informs his writing and that also endears him to people who hear his meticulously constructed homilies. The retired professor has helped out at area churches, including St. James in Syracuse and Immaculate Conception in Fayetteville.

Father Naumann does not generally deliver off-the-cuff homilies.

“Usually I write it out,” he said, “just to make sure I KNOW what I’m saying. And people realize that. They know that this has been worked on. And occasionally someone will say, ‘Oh, Father, I love your homilies because I always learn something,’ which is nice.”

Father Naumann actually gave homilies, too, when he taught at Canisius High School in Buffalo for 29 years.

Father Naumann picked up a knack for dialogue, description, and narration while at Canisius, because in addition to teaching English he also directed and appeared in plays and shows ranging from Shakespeare to “Fiddler on the Roof.”

A career as a writer was still in the future for the busy priest, teacher, and director. He attempted to write a high school murder mystery — “Everybody tries that” — and he had a victim but lacked other juicy elements, so he scrapped that.

After that long, rewarding career at Canisius, Father Naumann taught English for six years at Le Moyne College.

The minute he retired from teaching about 12 years ago, he started writing “all day long.”

There were rejections, but he kept at it. People had told him: “You should write something.” So he simply obeyed.

“Once I started writing, I realized I could do it,” he said.

He belongs to Wegmans Writers West, a group that meets to critique one another’s work in the guest conference room at the Jesuit Residence. They go over books such as Father Naumann’s longest book yet, The Other Side of the Light.

Asked if he’d like to be a kid again, climbing trees, Father Naumann said: “I know I can do without all of that.”

But he keeps reminding God of this: “You know, I haven’t finished my work that You gave me to do.”

And so, the readers of the world may want to pose the same question to him that Crispin’s brother Tarquin poses to him on page 57 of Crispin and the Great Tree:

“What new adventure are you going to dazzle me with this time?”

To order P.S. Naumann’s books:

Go to Amazon.com and look up P.S. Naumann.

Or go to his website, http://www.brothersbooksonline.com/

Father Naumann’s books also sold at the Le Moyne College bookstore